Merging K Sorted Arrays and Linked Lists

leetcode algorithm recursive divide and conquerConsider the following problem statements:

-

Given $k$ sorted contiguous arrays, return a single array containing all of the elements from each array in sorted order.

-

Given the heads to $k$ sorted linked lists, return a pointer to the head of a linked list containing all of the elements from each list in sorted order.

There are several different ways to merge $k$ sorted contiguous arrays or linked lists into one

sorted structure. In this post, I’ll mainly be covering a method that takes advantage of a merge()

function similar to what we use in mergeSort() to merge two sorted arrays or linked lists. If you

are unfamiliar with the process of merging two sorted linked lists, check out my blog post

here where I describe in detail the logic

behind the algorithm.

For simplicity, let’s assume each list has an average of $n$ elements.

In C++, I’ll be using a vector<int> container to represent a contiguous

array and a generic struct to represent a list node.

// Sample list node

struct Node {

int data;

Node* next;

Node(int data, Node* next = NULL) : data(data), next(next) { }

};

Naive merging

One way to merge $k$ contiguous vectors is to create a final output vector,

finalList, and set it equal to the first of $k$ vectors. Then we can merge in each

remaining vector one at a time. To do this, we set finalList = mergeLists(someList, finalList);

for all vectors. Consider the following code:

vector<int> mergeInefficient(const vector<vector<int> >& multiList) {

vector<int> finalList = multiList[0];

for (int j = 1; j < multiList.size(); ++j) {

finalList = mergeLists(multiList[j], finalList);

}

return finalList;

}

The code below applies to linked lists, given you have a function to merge two linked lists. Again, this post covers that algorithm separately.

Node* mergeInefficient(vector<Node*>& multiList) {

Node* finalList = multiList[0];

for (int j = 1; j < multiList.size(); ++j) {

finalList = mergeLists(multiList[j], finalList);

}

return finalList;

}

The merging in this method is very inefficient. Remember that the mergeLists() function

requires time (and space when merging arrays) asymptotically linear to the total number of

elements in both input lists. Since our finalList grows by $O(n)$ elements with each call

to mergeLists(), we’re getting the worst merging complexity every time we use it. Our first

merge will be $O(2n)$, our second merge will be $O(3n)$, and our final merge will be $O(nk)$.

Summing all of this up gives us the following complexity:

Naive selecting (vector implementation)

The logic behind this algorithm is fairly simple and inefficient. Basically, we

want to start with the first value of each of the $k$ vectors, pick the smallest

value, and push it to our finalList vector. We then need to increment the index we’re

keeping for the vector we just took the min value from. This implies that we need

to keep some state of our progress made with each vector. A vector of vector iterators

is used to hold our position in each of the $k$ vectors. While all iterators are not at

the .end() of their corresponding list, we maintain a minValue variable, initialized

to INT_MAX, and a minValueIndex variable. We then iterate over each of the $k$ vector

iterators and if the current iterator is not at an end position, we check to see if it is

smaller than our minValue. If it is, we update our minValue and set minValueIndex

(this is so we later know which iterator to increment when we’re done with one pass).

We do a check after our iteration to see if $minValue = \text{INT_MAX}$. If so, that

means all of the iterators must’ve been at their end position and minValue never got updated.

This means there were no real values left and we can stop. Regarding the complexity of this method,

we are iterating over $k$ vectors as long as there is one value that has not been added to our final

output. Since there are $O(nk)$ values, where $n$ is the average number of elements in each list, the

time complexity $= O(nk^2)$ like our other naive method.

An optimized approach to this method would be to maintain a min heap containing all of the first elements of each vector, from which we then pick the smallest one. This would drop the time complexity down to $O(nk\log(k))$, which we’ll see is the best we can do.

Consider the following implementation for vectors:

vector<int> mergeInefficientV2(const vector<vector<int> >& multiList) {

vector<int> finalList;

vector<vector<int>::const_iterator> iterators(multiList.size());

// Set all iterators to the beginning of their corresponding vectors in multiList

for (int i = 0; i < multiList.size(); ++i) iterators[i] = multiList[i].begin();

int k = 0, minValue, minValueIndex;

while (1) {

minValue = INT_MAX;

for (int i = 0; i < iterators.size(); ++i){

if (iterators[i] == multiList[i].end()) continue;

if (*iterators[i] < minValue) {

minValue = *iterators[i];

minValueIndex = i;

}

}

iterators[minValueIndex]++;

if (minValue == INT_MAX) break;

finalList.push_back(minValue);

}

return finalList;

}

Pairwise merging in $O(nk\log(k))$

The goal is to perform as many pairwise merges of the same size as we can before we start merging lists of a larger size. This allows us to keep the size of each list at a minimum. As a result, we don’t have one massive list and a bunch small ones.

Finally an optimized approach! The key to improving our time complexity when taking advantage of

a merge function is to call mergeLists() with the smallest input lists we can. After

calling mergeLists() once, some list has gotten $O(n)$ elements longer. Instead of calling

mergeLists() with this longer list, we’d be better off merging two smaller ones so we can

spread out the increasing lengths more evenly. The goal is to perform as many pairwise merges

of the same size as we can before we start merging lists of a larger size. This keeps the size

of each list at a minimum. We continue doing this until we merge $2$ lists of size $\frac{nk}{2}$

into our final structure. In fact, this idea of pairwise merging is exactly how mergeSort gets

its $\Theta(n\log(n))$ time complexity.

It is important to realize the total number of calls to the merge function will be the same as

the previous naive method utilizing mergeLists(). The difference lies within the sizes of

the lists we pass into the merge method. Pairwise merging allows us to minimize the heavy lifting

by only merging large lists when there are no smaller ones to merge. One way to look at its complexity

is sum up all of the lists we’re merging:

The total amount of work in each term is $nk$ because there are always $nk$ elements at play. However, we’re only doing $nk$ work $\log(k)$ times. Thus making this version of the algorithm, $O(nk\log(k))$, a much more favorable time complexity.

An iterative vector implementation simulating the divide and conquer process that mergeSort uses can be found below:

vector<int> mergeDivideAndConquer(vector<vector<int> > multiList) {

int l = 0, r = multiList.size()-1;

while (multiList.size() > 1) {

multiList[l] = mergeLists(multiList[l], multiList[r]);

multiList.pop_back();

l++;

r = multiList.size()-1;

if (r <= l) l = 0;

}

return multiList[0];

}

The code is essentially the same for linked lists:

Node* mergeDivideAndConquer(vector<Node*> multiList) {

if (!multiList.size()) return NULL;

int l = 0, r = multiList.size()-1;

while (multiList.size() > 1) {

multiList[l] = mergeLists(multiList[l], multiList[r]);

multiList.pop_back();

l++;

r = multiList.size()-1;

if (r <= l) l = 0;

}

return multiList[0];

}

Sorting

The easiest solution is to create some list and fill it with every value in every given sorted list. We then sort the list and we’re done. Since each sorted list contains an average of $n$ elements, the total number of elements we’d be sorting is $nk$. This means the time complexity after sorting is $O(nk\log(nk))$.

You can see that our pairwise merging solution essentially does this. However, instead breaking the list down into each single element (which by definition is sorted), the pairwise merging solution treats each sorted list as its own element. Thus, instead of having to merge $nk$ elements, we start with only $k$ elements (lists) that we have to merge. This is why the variable inside the $\log(x)$ differs in the complexity between the two versions.

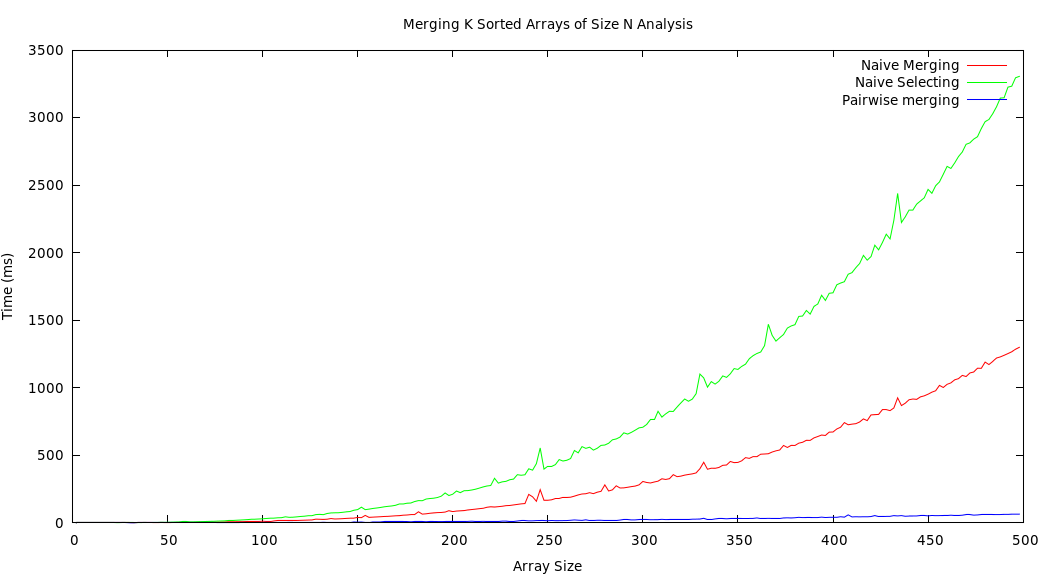

Analysis

The following plot shows the results I received after running a randomized test in which I generate a multidimensional vector of sorted vectors. Each iteration, both the multidimensional vector and each sub-vector increase in length by two elements. I then timed how long it took each solution to perform on the randomized input and produced the plot below: