What it takes to learn something

life algorithm runningWhen you see the fundamentals more clearly, you can build better solutions on your own…

While on my run the other day, I began thinking about what it actually takes to learn something, to master a

particular field of study. I started by trying to objectively measure my progress on some technical things

I’ve been working on. I looked at some of the paths I’ve taken to attain knowledge in certain areas and realized

they are almost all very winding, unpredictable, but thorough and rigorous. I then compared this to the path a

typical technical book urges you to take. Often it is very linear and tactfully thorough, like a recipe book. I

use the term tactfully thorough because many books only have you rip apart a problem to see its internals and

fundamentals at use if it goes together nicely with something used later in the text. The problem with this is

that you’re only truly experimenting inside a sandbox of which the boundaries are the author’s wishes.

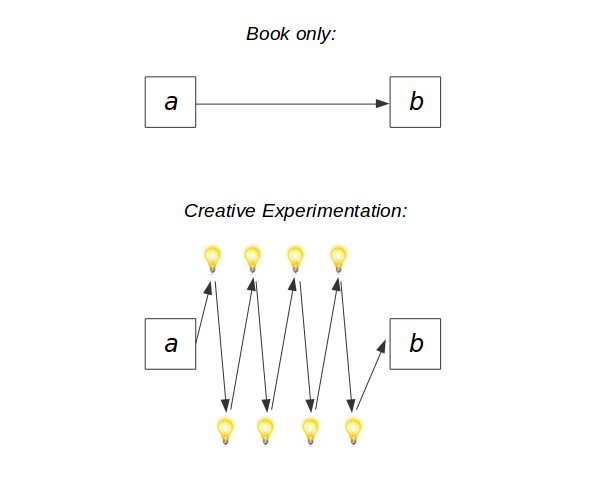

So who are these authors? Often a book will be chosen due to some achievements attributed to the author, thus giving them some measure of notoriety and/or credibility. In other words, they are someone who has made it in the field you’re in. There’s certainly nothing wrong with reading a book to gain information, but what I’ve found is often people treat a book like school. They only follow the curriculum, or in this case, the outline of each chapter which, in my opinion, defines the bare essentials at best. Books provide a good definition of what “point $a$” is and what accepted methods have yielded in a “point $b$”. The problem I have with this is that there is a lot more real estate between $a$ and $b$ than most instructive texts let on.

To demonstrate a mastery of fundamentals, you must traverse as much ground between $a$ and $b$ as you can. In other words, after getting the answer (either by yourself or from some source) never move on until you’ve absolutely beaten it to death. To understand exactly why the solution is what it is and why it works, you must see why every component of the solution needs to be there. Take the problem and change it up a bit. Stress the conditions of the solution to see exactly why/how it works, and under what conditions it will fail. Don’t take something as it is; prove to yourself its functionality. When you do this you see the fundamentals more clearly and, when you see the fundamentals more clearly, you can build better solutions on your own. After all, elaborate solutions are often just a clever construction of fundamentals.

To understand why these methods differ from just reading a book, we must understand the vehicle that books use to get information across. This vehicle is language. We have developed language as a way to get what is in our heads out to the world. The problem is this transfer is not $1 \Rightarrow 1$. In fact, much of what we try to express is lost when we cast our thoughts into our native tongue. Even more of the original thought process is lost when someone tries to interpret language, thus making langauge not the ideal vehicle for the transference of intuition.

Some lessons simply must be experienced to be understood. Information in a book is often a linguistic attempt to transfer organic knowledge and persistent mental connection, which is best formed when the brain figures something out (similar to a light bulb moment). True learning requires an experience as close to a natural discovery as possible. This is only possible by meticulously and holistically understanding the fundamentals that appear in so many problems over and over again. After all, how do we even have those light bulb moments? Our subconscious pieces together bits of known information to make a solution in the background. Often this known information can be utilized with a thorough understanding of the basics.